“Lo, I am with you always, even unto the end …”

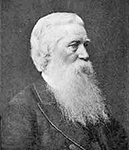

I can see him now, as stately and patriarchal; he walked up the desk room of the old college to address us. As that impressive and striking figure appeared at the door, every student instinctively sprang to his feet and remained standing till the Grand Old Man was seated. I thought that I had never seen a face more beautiful, a figure more picturesque. As visitation from another world could scarcely have proved more arresting or awe-inspiring. When it was announced that Dr. J. G. Paton, the veteran missionary to the New Hebrides, was coming to address the college, I expected to hear something thrilling and affecting; but somehow it did not occur to me that my eyes would be captivated as well. But, when the hero of my dreams appeared, a picture which I shall carry with me to my dying day was added to the gallery which my memory treasures.

‘In his private conversation,’ writes his son, ‘in his private conversation and in his public addresses, my father was constantly quoting the words, “Lo I am with you always”, as the inspiration of his quietness and confidence in the time of danger, and of his hope in the face of human impossibilities. So much was this realized by his family that we decided to inscribe that text upon his tomb in the Boroondara Cemetery. It seemed to all of us to sum up the essential element in his faith, and the supreme source of his courage and endurance.’

God’s great sunrise broke upon J.G. Paton amidst the sanctities and simplicities of his Scottish home. He was only a boy when he learned the sublime secret to which the text gives expression, and it was his father who revealed it to him. In a passage that has taken its place among our spiritual classics, he has described the little Dumfriesshire cottage, with its ‘but’ and its ‘ben’, and the tiny apartment in which he used to hear his father at prayer. And whenever the good man issued from that cottage sanctuary, there was a light in his face which, Dr. Paton says, the outside world could never understand; ‘but we children knew that it was a reflection of the Divine Presence in which his life was lived.

And continuing this touching story, Dr. Paton describes the impression that his father’s prayers in that little room made upon his boyish mind. ‘Never,’ he says, ‘in temple or cathedral, on mountain or in glen, can I hope to feel that the Lord God is more near, more visibly walking and talking with men, than under that humble cottage roof of thatch and oaken wattles. Though everything else in religion were by some unthinkable catastrophe to be swept out of memory, my soul would wander back to those early scenes, and would shut itself up once again in that sanctuary closet, and hearing still the echoes of those cries to God, would hurl back all doubt with the victorious appeal: He walked with God; why may not I?’

Why, indeed? J. G. Paton resolved that his father’s religion should be his religion; his father’s God his God. Thus, then, J. G. Paton, as a boy in his Scottish home, learned the unutterable value of the text “Lo, I am with you always.” Thus, too, twenty years later, he went out to his life-work, singing in his soul those golden words.

He very quickly tested their efficacy and power. It was on the fifth of November 1858 that the young Scotsman and his wife first landed on Tanna. It was purely a cannibal island in those days, and the white man found his faith in his text severely tried. ‘My first impressions,’ he tells us, ‘drove me to the verge of utter dismay. On beholding the natives in their pain and nakedness and misery, my heart was full of horror as of pity. Had I given up my much-beloved work, and my dear people in Glasgow, with so many delightful associations, to consecrate my life to these degraded creatures?

Was it possible to teach them right and wrong, to Christianize, or even to civilize them?

If ever a man seemed lonely J. G. Paton seemed lonely when, three months later, he had to dig with his own hands a grave for his young wife and his baby boy. In spite of all pleas and remonstrances, Mrs. Paton had insisted on accompanying him, and now, the only white man on the island, he was compelled to lay her to rest on this savage spot. ‘Let those,’ he says, ‘who have never passed through similar darkness – darkness as of midnight – feel for me; as for all others, it would be more than vain to try to paint my sorrows. I was stunned: my reason seemed almost to give way: I built a wall of coral round the grave, and covered the top with beautiful white coral, broken small as gravel; and that spot became my sacred and much-frequented shrine during all the years that, amidst difficulties, dangers, and deaths, I laboured for the salvation of these savage islanders. Whenever Tanna turns to the Lord and is won for Christ, men will find the memory of that spot still green. It was there that I claimed for God the land in which I had buried my dead with faith and hope.’

With faith and hope! What faith? What hope? It was the faith and the hope of his text! “Lo, I am with you alway” ‘I was never altogether forsaken,’ he says in his story of that dreadful time, ‘The ever-merciful Lord sustained me to lay the precious dust of my loved ones in the same quiet grave. But for Jesus, and the fellowship He vouchsafed me there, I must have gone mad and died beside that lonely grave.’

It was thus, at the very outset of his illustrious career, that Dr. Paton discovered the divine dependability of his text.

Through the eventful years that followed, the text was his constant companion. He faces death in a hundred forms, but the episode invariably closes with some such record as this:

During the crisis, I felt generally calm and firm of soul, standing erect and with my whole weight on the promise, “Lo I am with you alway”. Precious promise! How often I adore Jesus for it and rejoice in it! Blessed be His name! Or this:

‘I have always felt that His promise, “Lo I am with you alway” is a reality, and that He is with His servants to support and bless them even unto the end of the world.’

In 1862 the whole island was convulsed by tribal warfare. In their frenzy the natives threatened to destroy both the mission station and the missionary. Nowar, a friendly chief, urged Dr. Paton to fly into the bush and hide in a large chestnut-tree there. ‘The hours that I spent in that chestnut-tree,’ writes Dr. Paton, ‘still live before me. I heard the frequent discharge of muskets and the hideous yells of the savages. Yet never, in all my sorrows, did my Lord draw nearer to me.’

About midnight a messenger came to advise him to go down to the beach. ‘Pleading for my Lord’s continued presence, I could but obey. My life now hung on a very slender thread. But my comfort and joy sprang from the words, “Lo I am with you alway”. Pleading this promise I followed my guide.’

‘I confess,’ Dr. Paton says, ‘that I often felt my brain reeling, my sight coming and going, and my knees smiting together when thus brought face to face with a violent death. Still, I was never left without hearing that promise coming up through the darkness and the anguish in all its consoling and supporting power: “Lo, I am with you always.”’

Some years later, Dr. Paton married again, and settled at Aniwa. But on a notable occasion, he revisited Tanna. Old Nowar was delighted, and begged them to remain. ‘We have plenty of food’ he assured Mrs. Paton. ‘While I have a yam or a banana, you shall not want.’ ‘Then’ says Dr. Paton, ‘he led us to that chestnut-tree in the branches of which I had sheltered during that lonely and memorable night when all hope of earthly deliverance had perished, and said to Mrs. Paton, with a manifest touch of genuine emotion, “The God who protected Missi in the tree will always protect you!”’

The Form in the Furnace – the Form that was like unto the Son of God – was seen by Nebuchadnezzar as well as by the Three Hebrew Children. And the presence of Him who had said, “Lo, I am with you alway” was recognized by the barbarians on Tanna, as well as by Dr. Paton himself. Their sharp eyes soon detected that the white man was never left to his own resources.

From The Wicket Gate Magazine, published in the UK, used with permission.