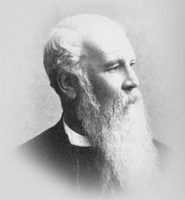

J.C. Ryle

J.C. Ryle

“Let your conversation be without covetousness; and be content with such things as ye have: for he hath said, I will never leave thee, nor forsake thee.” —Hebrews 13:5

Nothing is cheaper than good advice. Everybody fancies he can give his neighbor good counsel and tell him exactly what he ought to do. Yet to practice the lesson that heads this paper is very hard. To talk of contentment in the day of health and prosperity is easy enough; but to be content in the midst of poverty, sickness, trouble, disappointments, and losses is a state of mind to which very few can attain.

Let us turn to the Bible and see how it treats this great duty of contentment. Let us mark how the great Apostle of the Gentiles speaks when he would persuade the Hebrew Christians to be content. He backs up his injunction30 by a beautiful motive. He does not say nakedly, “Be content.” He adds words that would ring in the ears of all who read his letter and nerve their hearts31 for a struggle: “Be content,” he says, “with such things as ye have: for he hath said, I will never leave thee, nor forsake thee.”

Reader, I see things in this golden sentence, I venture to think, that deserve special notice. Give me your attention for a few minutes, and we will try to find out what they are.

Let us first examine the precept that St. Paul gives us: “Be content with such things as ye have.” These words are very simple. A little child might easily understand them. They contain no high doctrine; they involve no deep metaphysical question;32 and yet, simple as they are, the duty that these words enjoin on us is one of the highest practical importance to all classes.

Contentment is one of the rarest graces. Like all precious things, it is most uncommon. The old Puritan divine,33 who wrote a book about it, did well to call his book The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment.34 An Athenian philosopher is said to have gone into the market place at midday with a lantern in order to find out an honest man. I think he would have found it equally difficult to find one quite contented.

Before they fell, the fallen angels had heaven itself to dwell in and the immediate presence and favor of God; but they were not content. Adam and Eve had the Garden of Eden to live in with a free grant of everything in it excepting one tree; but they were not content. Ahab had his throne and kingdom, but so long as Naboth’s vineyard was not his, he was not content. Haman was the chief favorite of the Persian king; but, so long as Mordecai sat at the gate, he was not content.

It is just the same everywhere in the present day. Murmuring, dissatisfaction, discontent with what we have—[these] meet us at every turn. To say with Jacob, “I have enough” (Gen 33:11), seems flatly contrary to the grain of human nature. To say, “I want more,” seems the mother tongue of every child of Adam. Our little ones around our family hearths are daily illustrations of the truth of what I am saying. They learn to ask for “more” much sooner than they learn to be satisfied. They are far more ready to cry for what they want, than to say, “Thank you,” when they have [received] it.

There are few readers of this very paper, I will venture to say, who do not want something or other different from what they have—something more or something less. What you have does not seem as good as what you have not. If you only had this or that thing granted, you fancy you would be quite happy.

Hear now with what power St. Paul’s direction ought to come to all our consciences: “Be content,” he says, “with such things as ye have” —not with such things as ye once used to have, not with such things as ye hope to have, but with such things as ye have now. With such things, whatever they may be, we are to be content—with such a dwelling, such a position, such health, such income, such work, such circumstances as we have, we are to be content…To be content is to be rich and well-off. He is the rich man who has no wants and requires no more. I ask not what his income may be. A man may be rich in a cottage and poor in a palace.

To be content is to be independent. He is the independent man who hangs on no created things for comfort and has God for his portion. Such a man is the only one who is always happy. Nothing can come amiss or go wrong with such a man. Afflictions will not shake him, and sickness will not disturb his peace. He can gather grapes from thorns and figs from thistles, for he can get good out of evil. Like Paul and Silas, he will sing in prison with his feet fast in the stocks. Like Peter, he will sleep quietly in prospect of death the very night before his execution. Like Job, he will bless the Lord even when stripped of all his comforts.

Ah! Reader, if you would be truly happy—who does not want this?—seek it where alone it can be found. Seek it not in money. Seek it not in pleasure, in friends, or in learning. Seek it in having a will in perfect harmony with the will of God. Seek it in studying to be content.

You may say, “It is fine talking: how can we be always content in such a world?” I answer that you need to cast away your pride and know your deserts35 in order to be thankful in any condition. If men really knew that they deserve nothing and are debtors to God’s mercy every day, they would soon cease to complain. You may say, perhaps, that you have such crosses, trials, and troubles that it is impossible to be content. I answer that you would do well to remember your ignorance. Do you know best what is good for you or does God? Are you wiser than He is?

The things you want might ruin your soul. The things you have lost might have poisoned you. Remember, Rachel must needs36 have children: she had them and died (Gen 30:1; 35:16-19). Lot must needs live near Sodom, and all his goods were burned. Let these things sink down into your heart.

___

From Shall We Know One Another and Other Papers, published by Charles Nolan Publishers, www.charlesnolanpublishers.com.

30. injunction – authoritative order.

31. nerve their hearts – muster courage or self-control in preparation for something difficult.

32. metaphysical question – philosophical first principle such as being, space, time, etc.

33. Jeremiah Burroughs (1599-1647) – Congregational preacher and member of the Westminster Assembly of Divines. (See previous article.)

34. Available in an abridged booklet from CHAPEL LIBRARY.

35. deserts – what one deserves with regard to reward or punishment.

36. needs – of necessity.

J. C. Ryle (1816-1900): Bishop of the Anglican Church; born at Macclesfield, Cheshire County, England.

Courtesy of Chapel Library