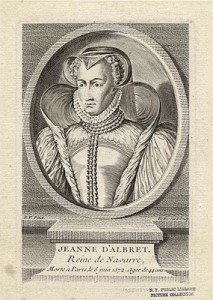

Historians have characterized Queen Jeanne d’Albret of Navarre (1528-1572) as remarkable, grave, saintly, inspiring, brave, ardent and strong-willed. Indeed, she was a woman of distinguished valour. But even more than that, she was faithful to the cause of Christ and his church in an age when faithfulness was very costly.

Princess Jeanne, the only child of King Henry II of Navarre and Marguerite d’Angouleme, was born to great wealth and privilege. Not only was her father a king, but her uncle, Marguerite’s brother, was King Francis I of France. Consequently, Jeanne was an heiress of much of southwestern France on her father’s side of the family, and a Princess of the Blood on her mother’s side. Of particular interest to Reformation scholars is Jeanne’s mother. Marguerite was a woman of exceptional mind, refined manners and, while never officially breaking with the church of Rome, took personal interest in the evangelical religion which was rapidly spreading throughout France. Her private chaplain was Gerard Roussel (d.1555), Bishop of Oloron, critic of the Roman Catholic church and a preacher of the gospel. So much truth did he preach that he and Marguerite enraged the theological faculty of the Sorbonne. Intervention by her brother, the King, helped to defuse the difficult situation. However, at court in Nerac she continued to confer with the Reformers Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples and Clement Marot, and she also provided temporary refuge for William Farel, John Calvin and Theodore Beza.

The effect of these events upon the future Huguenot Queen Jeanne d’Albret cannot be underestimated. In a letter to Vicomte de Gourdon, August of 1555, the twenty-seven-year-old Jeanne reminisces:

“I well remember the great annoyance shown years ago by most honoured farher and lord . . . when (my mother) was praying in her room with the ministers, Roussel and Farel . . . how he slapped her on the cheek and forbade her to meddle in doctrinal matters – he shook a stick at me, which has cost me bitter tears and kept me fearful and compliant until they had both died.”

Jeanne was probably six years old at the time and much impressed that her mother’s evangelical views were at the least unsafe, if not outright dangerous. It is clear that her later profession of faith was not something which was entered into recklessly or casually.

In 1548, Princess Jeanne was married (an earlier unconsummated marriage having been annulled) to Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendome, and ‘First Prince of the Blood’, indicating that he was next in line to the French throne after the sons of Henry II, provided they had no male heirs. His illustrious military exploits against Charles V earned him a peerage from Francis I in 1544 at the age of twenty-six. Mihieli, the Venetian ambassador describes Antoine as ‘famed for his courage in battle, though rather as a fine soldier than as a great commander. He is nevertheless regarded as one of the ablest princes in the Kingdom’. Yet there is little to admire in Antoine other than military prowess. For Jeanne the union was unhappy. Her husband was unfaithful to their marriage, unfaithful to the evangelical cause, and ultimately showed himself to be a vain and frivolous man. Nonetheless the union of Antoine and Jeanne brought forth six children, two of whom survived, a daughter and a future King of France, the renowned Henry IV. Her mother had died earlier when Jeanne was twenty-one years of age.

Jeanne became Queen of Navarre when her father, the King, passed away in the spring of 1555. Her correspondence suggests an interest in the Reformed faith dating from about this time, but as her biographer Nancy Roelker relates ‘the inclination did not crystallize into conviction until 1560, when the outer circumstances of her life reinforced it and precipitated a decision’. The ‘outer circumstances’ were the disappointments encountered in her marriage, political threats to her kingdom and the preaching and teaching of Theodore Beza.

In January 1561 John Calvin, the Genevan reformer and preacher, wrote his first letter to the Queen of Navarre saluting her fortitude in the face of opposition and disappointment: ‘I know that you do not need my advice . . . to take arms and do battle against the . . . difficulties that will assail you’. Referring to the work of Beza he writes, ‘who . . . sowed good seed in you . . . although it was almost choked by the thorns of worldliness . . . God in his infinite goodness has prevented it . . . from disappearing altogether’. Calvin continues to exhort her to duty, but then leaves off stating ‘When I see how the Spirit of God rules you I have more occasion to give thanks than to exhort you’. He alludes, carefully to their disappointment in Antoine, ‘For a long time we have tried to do our duty by the King, your husband . . . as you will see again from the enclosed copy of a letter we have sent him’. The English Queen, Elizabeth I, also sent her felicitations regarding Jeanne’s ‘affection for the true religion’ along with her hopes that the Queen of Navarre would make the most of her fortunes: ‘The present offers great opportunities to encourage those well-disposed’, and with reference to Antoine and other false professors that ‘the enemy should not be aided by the indifference or lukewarm attitude of its professors’.

Queen Jeanne d’Albret’s course was set. She henceforth lived a life of faithfulness to her covenant God. During the next twelve years of her life counter-Reformation forces made earnest efforts to discredit and destroy her. Arrayed against her were many of the great nobles of France, the Papacy, King Philip of Spain and others. The French crown, especially under the influential Catherine de Medici, whom we could identify as Machiavelli’s The Prince by her duplicity to play Huguenot against Catholic, once cajoled Jeanne to return to the Roman Catholic church that she might save her kingdom for her son Henry. The Queen of Navarre resolutely declared: ‘Madame, if I at this very moment held my son and all the kingdoms of the world together, I would hurl them to the bottom of the sea rather than peril the salvation of my soul’. This faithful Queen was willing to give up the two things most precious to her: her kingdom and her son, and like Abraham with Isaac – she loved God above all things.

After the death of Antoine at the siege of Rouen in 1562, she acquired greater freedom to serve the cause of God and truth in her own realm. Her first act was the publication of an edict establishing the practice of the Reformed faith in Beam, her capital, and to prohibit the exercise of Roman Catholic worship. Severe was the Pope’s displeasure toward her bold act. A special papal emissary from Trent, the Cardinal d’Armagnac, came to warn the erring Huguenot Queen of dire consequences if she pursued her present religious policy. Jeanne responded to his letter with courage and clarity:

“I condemn no one to death or to imprisonment, which penalties are the nerves and sinews of a system of terror – I blush for you, and feel ashamed when you falsely state that so many atrocities have been perpetrated by those of our religion. Purge the earth first from the blood of so many just men shed by you and yours. Pull that mote from your own eye, and then you shall see to cast the beam out of thy neighbour’s . . . You excuse yourself, and allege your authority over these countries as the Pope’s Legate. I receive here no Legate at the price which has cost France. I acknowledge over me in Bearn God only, to whom I shall render account of the people he has committed to my care. As in no point I have deviated from the faith of God’s Holy Catholic church, nor quitted her fold, I bid you keep your tears to deplore your own errors . . . that you may be restored to the true fold, and become a faithful shepherd instead of a hireling. I desire that your useless letter may be the last of its kind.”

Her response to the papal envoy was published and circulated throughout France. Pope Gregory VII was enraged, and in October of 1563 published a bull which threatened her excommunication and the loss of her kingdom. She was ordered to appear before the Inquisition at Rome. Jeanne made an appeal to the French court which saw its interests served by keeping the Pope out of French politics. Ensuing political pressure caused Gregory to withdraw his bull.

Soon a conspiracy was hatched by His Most Catholic Majesty, King Philip II of Spain, to kidnap Jeanne and transport her to Spain with the purpose of having the Inquisition condemn her for heresy. The widowed Queen had earlier refused Philip’s suggestion that she marry his son. The plot failed, allowing the Queen to flee to her fortress at Navarreins. Reflecting upon the incident in a letter to a friend, she wrote, ‘Although I am just a little princess, God has given me the government of this country, so that I might rule it according to his Gospel and teach it his laws. I rely on God who is more powerful than the King of Spain’.

The remaining years of her life were spent furthering the gospel in her domains and throughout France. Deeply loved by her subjects, this faithful Huguenot Queen reformed the laws of her land, gave aid and assistance to the poor, and established colleges to train theological students in the Reformed faith. Under her personal supervision the Bible was translated into the dialects of southern France. She used her wealth, including the mortgaging of her jewels to bring in and support Reformed pastors to preach the gospel. She took the gospel with her wherever she went. In Paris’ the stronghold of Catholicism, she would have Huguenot preachers declare the Word of God in the royal apartment inviting the court to listen. After the outbreak of the religious wars in France, she advised and lent assistance to the Protestant war effort in administration, nursing, the building of fortifications and composing pamphlets supporting the Protestant cause.

William Hanna, in his Wars of the Huguenots describes Queen Jeanne d’Albret as the ‘wisest and most enlightened sovereign of her age’. Her life is marked by courage in the face of adversity. She outlived four of her six children; her husband was not faithful to her, nor to the cause of the gospel. Antoine, unhappy that Jeanne would not return to the old religion, took her two surviving children from her to be tutored by Roman Catholic teachers. Yet, she was intractable in refusing to renounce her faith for worldly or domestlc gain.

The end came on Monday morning, 9 June 1572, after many years of illness. The day before had been spent by Jeanne in prayer, listening to expositions of Scripture and, as she had requested, the reading of Psalm 31 and the Gospel of John chapters fourteen through to eighteen. She was fortyfour years of age when she died. Her last instructions were to be conveyed to her son and daughter: ‘Tell my son that I desire him, as the last expression of my heart, to persevere in the faith in which he has been brought up’. Her heart was spared from the agony that her son, the future King of France, would later become an apostate. She was reputed to have prayed just before she died, ‘O my Saviour, hasten to deliver my spirit from the miseries of this life, and from the prison of this suffering body, that I may offend thee no more, and enter joyfully into that rest which thou hast promised and that my soul so longs for’.

What great lessons might we learn from the life of this most faithful and courageous woman? First, to continue faithful to the gospel and to Jesus Christ, undergoing any sacrifice which he requires. From her public profession of faith, until her death twelve years later, her life was a ‘living sacrifice’ offered to God. She was willing to give all for the Lord Jesus Christ. She obeyed the Saviour’s words: ‘He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. And he that doth not take his cross and follow after me, is not worthy of me. He that findeth his life shall lose it; and he that loseth his life for my sake shall find it’ (Matt. 10:37-39).

Secondly, we must learn to trust God in all circumstances. The whole of the Christian life must be given to learning to trust God more and more. Faith in God is the root which nourishes the Christian to withstand the afflictions and vicissitudes of life in this world. Trust in God gives courage to weak and sinful men to risk all in the cause of Jesus Christ. Jeanne d’Albret is an example of a Christian woman who, in spite of all the forces arrayed against her, persevered to the end. Many times she found comfort and courage from the thirteenth verse of her favourite psalm, Psalm 31: ‘I had fainted, unless I had believed to see the goodness of Jehovah in the land of the living’.

May the memory of God’s grace in the life of this Huguenot Queen be an encouragement to each one of us.